Most developers treat their tools as black boxes. Code goes in, magic happens, executable comes out. I was the same way — until a video game pushed me to open one up.

This is the story of how Stationeers, arguably the hardest game I've ever played, led me to build a compiler from scratch. Not because I had to. Because I wanted to understand.

The game that broke my brain

Stationeers is a space survival simulation where you manage atmospheric systems, power grids, and manufacturing chains. Think Factorio, but instead of conveyor belts you're dealing with gas mixtures, pressure differentials, and thermodynamics.

Here's the thing that makes it special: every device in the game — sensors, valves, pumps, displays — can be programmed using IC10, a custom assembly language. You're essentially doing embedded systems programming inside a video game.

Want to automate your base's cooling system? You need to write code that reads temperature sensors, calculates the optimal valve positions, handles edge cases when pressure drops, and coordinates multiple devices working in parallel.

It's a sandbox for learning how real industrial automation works. Except when you mess up, your character suffocates instead of a factory burning down.

The problem with assembly

Assembly languages are simple by design. That's kind of the point — you're one step above machine code. IC10 is no exception.

You get 16 registers, basic math, conditionals, and device I/O. No functions. No stack (well, there's a limited one). No abstractions.

Even conditionals don't work the way you'd expect. There's no if temperature < 293 then. Instead, comparison instructions just store 0 or 1 into a register, and then you branch based on that value. Your brain has to translate "if X is less than Y" into "compute whether X < Y, store the boolean, then jump if that boolean is non-zero."

Here's what a simple temperature check looks like:

l r0 TemperatureSensor Temperature

slt r1 r0 293

bgtz r1 TooCold

# ... handle normal temperature

j End

TooCold:

# ... activate heater

End:

For small scripts, this is fine. But my automation ambitions grew. Cooling system for gas processing? That requires reading multiple sensors, comparing values, managing state across loop iterations, handling different gas types differently.

Suddenly I was bumping against the 128-line limit, losing track of which register held what, and introducing bugs every time I made changes.

I needed a better language.

The first instinct: find an existing solution

Like any reasonable developer, I first looked for existing tools. There were a few:

- A visual block-based programming tool

- A couple of C-like language compilers

- Some preprocessors that added macros

They worked. Kind of. But they all felt like band-aids. More importantly, they were black boxes too — I couldn't fix issues or add features I needed.

Then a thought crept in: What if I built my own?

Why not just use an existing tool?

I could give you practical reasons. The existing compilers didn't support features I wanted. They had bugs. The codebases were hard to contribute to.

But honestly? I was curious.

I'd been writing software professionally for years. I'd used countless compilers, transpilers, and code generators. Yet I had no real understanding of how they worked. The transformation from "human-readable code" to "machine instructions" was pure magic to me.

Stationeers gave me a perfect excuse to demystify that magic. The target was simple enough (16 registers, ~50 instructions) that I could build something real without getting lost in complexity. But it was real enough that I'd learn actual compiler concepts.

So I opened my editor, started a conversation with Claude Code, and began building.

Yes, I used AI throughout the process — as a learning partner and pair programmer. The code is mine, the decisions are mine, the bugs were definitely mine. But having AI to accelerate the learning curve made this project possible in months instead of years.

What I actually built

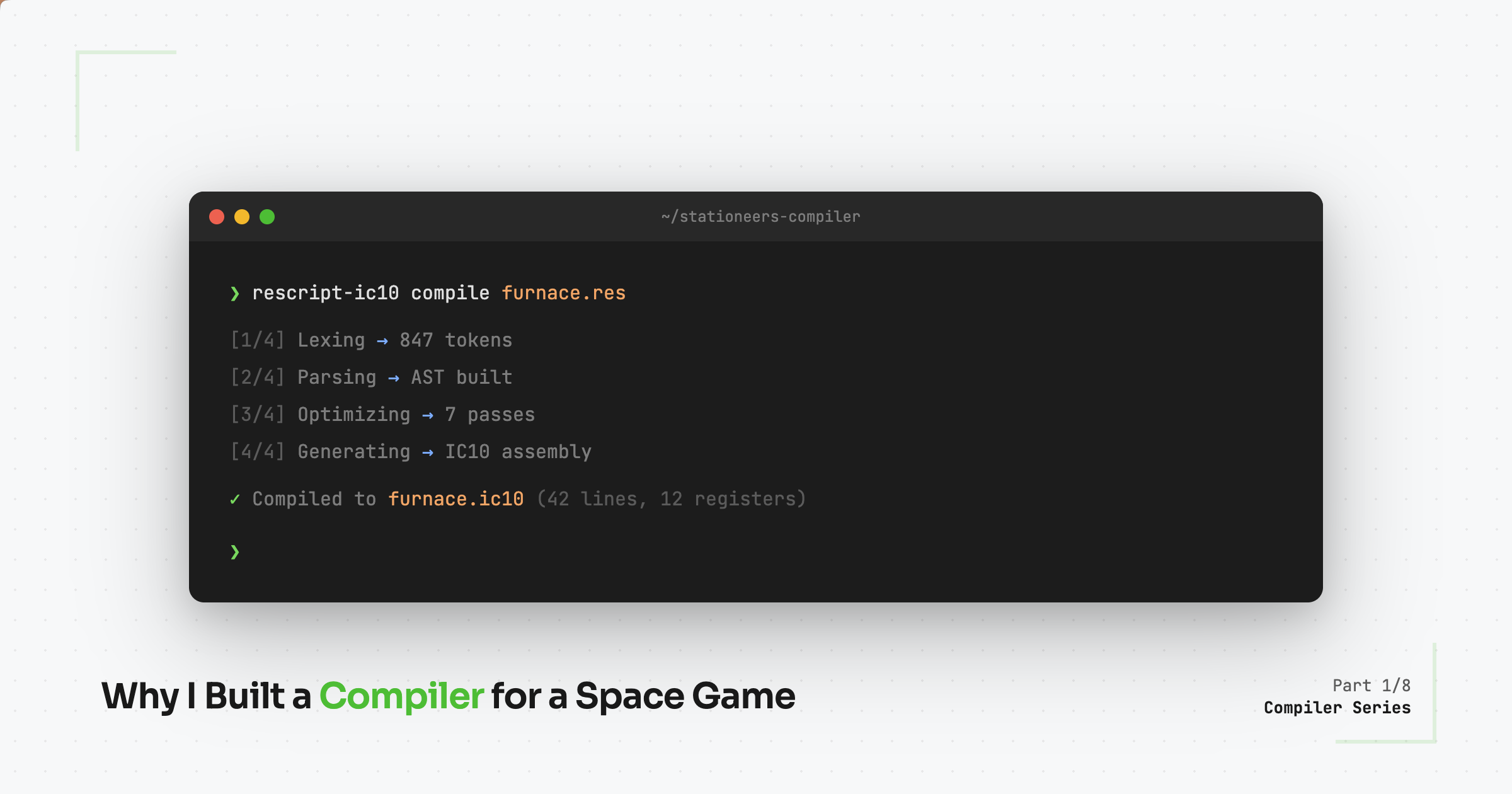

Fast forward a few months, and I have a working compiler that translates a subset of ReScript into IC10 assembly.

The pipeline looks like this:

ReScript Source

↓

Lexer → breaks code into tokens

↓

Parser → builds abstract syntax tree

↓

Optimizer → simplifies the tree

↓

IR Generator → creates intermediate representation

↓

IR Optimizer → 7 optimization passes

↓

Code Generator → outputs IC10 assembly

I can now write this:

let furnace = device("d0")

let sensor = device("d1")

while true {

let temp = l(sensor, "Temperature")

if temp < 500 {

s(furnace, "On", 1)

} else {

s(furnace, "On", 0)

}

}

And get optimized assembly that runs on any IC10 chip in the game.

Why ReScript?

I could have invented my own syntax. But that would mean building a language and a compiler — two massive projects instead of one.

By choosing an existing language, I got:

- Ready-made tooling — syntax highlighting, LSP, autocomplete in my editor. All for free.

- Zero configuration — no arguing with myself about formatting rules or linter settings. ReScript has one way to format code, and that's it.

- A proven type system — Hindley-Milner type inference, battle-tested in OCaml and Haskell. Pattern matching, variants, strong typing. Designed by people smarter than me.

- Focus — I could spend my time on the interesting part (code generation) instead of bikeshedding syntax decisions.

The language I implemented is a subset: variables, arithmetic, conditionals, loops, mutable references, and — my favorite part — variant types with pattern matching.

The features that matter

Some things I'm particularly proud of:

Register allocation. IC10 gives you exactly 16 registers. My allocator tracks variable lifetimes and reuses registers efficiently. It took three rewrites to get right.

Branch optimization. Instead of computing boolean values and then branching, the compiler generates direct branch instructions. if x < y becomes blt r0 r1 label — no intermediate steps.

Pattern matching on variants. I can define state machines with data:

type state = Idle | Heating(int) | Cooling(int)

let state = ref(Idle)

while true {

let temp = l(sensor, "Temperature")

switch state.contents {

| Idle => state := Heating(temp)

| Heating(startTemp) =>

if temp > 500 { state := Idle }

else { heatCmd() }

| Cooling(startTemp) =>

if temp < 300 { state := Idle }

else { coolCmd() }

}

}

This compiles to efficient assembly with proper tag checking and value extraction.

Multi-backend architecture. The compiler now has an intermediate representation (IR) layer. I've already added a WebAssembly backend for testing outside the game. Adding new targets is straightforward.

What I learned (the real value)

Building a compiler taught me more about software engineering than any book or course:

Constraints breed creativity. 16 registers forced me to think carefully about resource allocation. No stack meant I had to be clever about nested expressions. These limitations made me a better problem solver.

Abstractions have costs. Every language feature I added meant more work for the code generator. I gained deep appreciation for why language designers make certain tradeoffs.

Testing is everything. I have 40+ test cases covering edge cases I never would have anticipated. The bug where all my conditionals were inverted? That taught me to test assumptions, not just happy paths.

Reading code is a skill. I spent hours reading other compiler implementations. Understanding existing solutions before building your own saves enormous time.

This is part 1 of a series

I'm planning to write about each phase of the compiler in detail:

- Why I Built a Compiler ← you are here

- Lexer: Breaking Code Into Tokens

- Parser: Building Trees From Tokens

- Register Allocation: Making 16 Registers Enough

- The Bug That Inverted All My Conditionals

- Adding State: Loops and Mutable References

- Pattern Matching: From Theory to Assembly

- Multi-Backend: Adding WebAssembly

Each post will include code, diagrams, and lessons learned. Whether you want to build your own compiler or just understand what happens when you hit "compile," I hope you'll find something useful.

The takeaway

Most developers will never need to build a compiler. But understanding how they work changes how you think about code.

When I write TypeScript now, I think about what the parser sees. When I debug performance issues, I consider what the optimizer might miss. When I design APIs, I think about how they'll be consumed by tools.

Stationeers gave me an excuse to go deep. The compiler gave me a new lens for seeing software.

Sometimes the best way to understand your tools is to build one yourself.

The compiler is open source. If you're curious, want to contribute, or just want to see if I'm making this up, check it out on GitHub.

Next up: how the lexer breaks source code into tokens, and why that's harder than it sounds.